Khurram A Khan

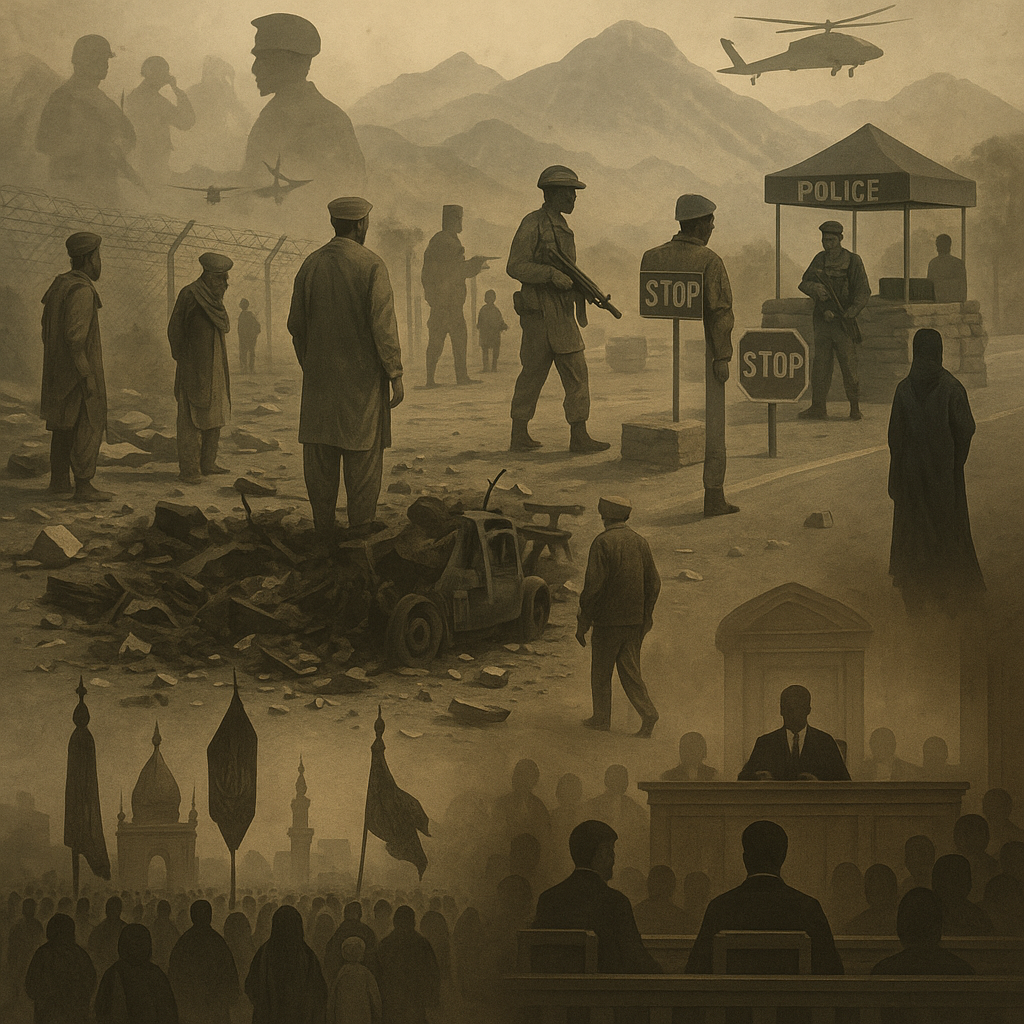

The government has proposed amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) of 1997, citing the need for a stronger legal framework to address current security threats. This amendment seeks to reintroduce provisions from 2014, allowing the government and armed forces to detain individuals posing significant risks to national security for up to three months.

Under the proposed changes, the government or military can “…. detain individuals who pose a significant threat to national security” with a sunset clause to lapse after two years of becoming operational for anyone connected to offences under the ATA, including target killings, kidnappings for ransom, and extortion. Detentions would be based on credible complaints or reasonable suspicion. An inquiry would be conducted by a Joint Interrogation Team (JIT) that includes police, intelligence, and military representatives.

The bill also stipulates that after three months, further detention must comply with Article 10 of the Constitution, which protects against arbitrary arrest. This article mandates that detainees must be presented before a magistrate within 24 hours or detained for three months subject to a Review Board’s oversight, consisting of judges from the Supreme Court or High Courts.

The 2014 amendments had simultaneously established military courts through a constitutional amendment for trials related to terrorism, particularly targeting Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) elements, and were linked to Operation Zarb-e-Azb. However, these measures lapsed in 2016.

The reinserted amendment would empower not just the government but also armed forces to detain individuals based on suspicion, ostensibly to prevent potential terrorist attacks and facilitate intelligence-gathering. The proposed law would allow for a three-month detention period before adhering to constitutional scrutiny with a sunset clause of two years validity.

The bill further reasons that preventive detention of the suspects would disrupt their plans to carry out terrorist attacks; provide law enforcement agencies the legal grounds to conduct more effective operations against the terrorists; and facilitate law enforcement agencies to glean actionable intelligence.

Originally enacted to combat sectarian violence in the late 1990s, the ATA has evolved to address both transnational terrorism and domestic threats. However, its effectiveness is often questioned. Intelligence-based operations (Kinetic Operations) frequently result in suspects being killed in crossfire rather than being arrested and tried in courts. Additionally, many arrested terror suspects are killed during police encounters while being transferred for investigations or trial, complicating accountability. Extra-judicial killings have become tool to punish someone perceived as a terrorist by the security apparatus without going through the rigours of judicial process.

Moreover, the law is sometimes applied indiscriminately to non-terrorism-related crimes, overburdening anti-terrorism courts with cases that do not meet the law’s intended focus. This broad application has led to its use against political opponents and activists, diluting its impact on genuine terrorism.

For the ATA to be effective, it must be restricted to its primary purpose: deterring and convicting those involved in terrorism and supporting proscribed organisations. The law should not be weaponized against individuals expressing dissent or seeking to assert their rights, as such misuse undermines its original intent to combat genuine threats.

The proposed amendments highlight concerns about using the law to detain individuals on mere suspicion and shifting burden of proof to Joint Interrogation Teams. The situation in former FATA’s internment centres, where detainees faced inhumane conditions, raises further alarms about the misuse of such powers. The case is to be heard by the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

The reality is that the practice of detaining suspects has been going on unabated and that has contributed significantly to the rise of enforced disappearances. The proposed amendment would legitimise a flawed practice that fails operationally too. It has been noted that terrorists and their associates often withhold valuable information when subjected to coercion, especially without sufficient context about their involvement. This was highlighted by Israel’s inability to foresee the October 7 attack by Hamas, despite having detained numerous Palestinians in internment centres. Lack of training in interrogation techniques particularly of personnel of armed forces and civil armed forces further impede desired outcome of the exercise. Their inability to discern between genuine and malicious information that would further lead to detaining innocent persons.

The author is the former Joint Director General Intelligence Bureau.